rack and tank film processing

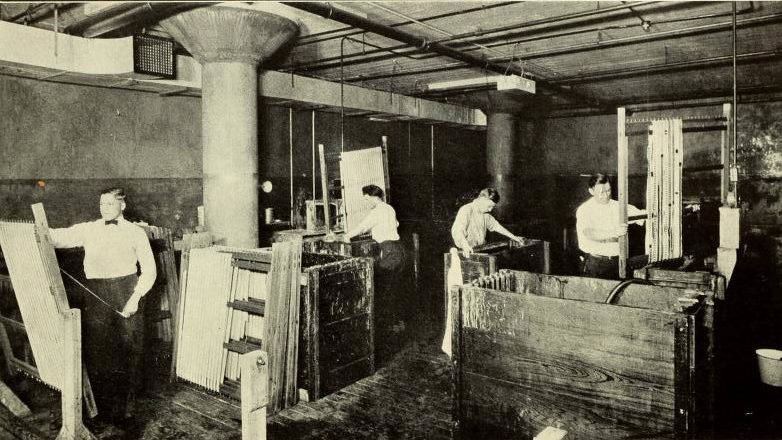

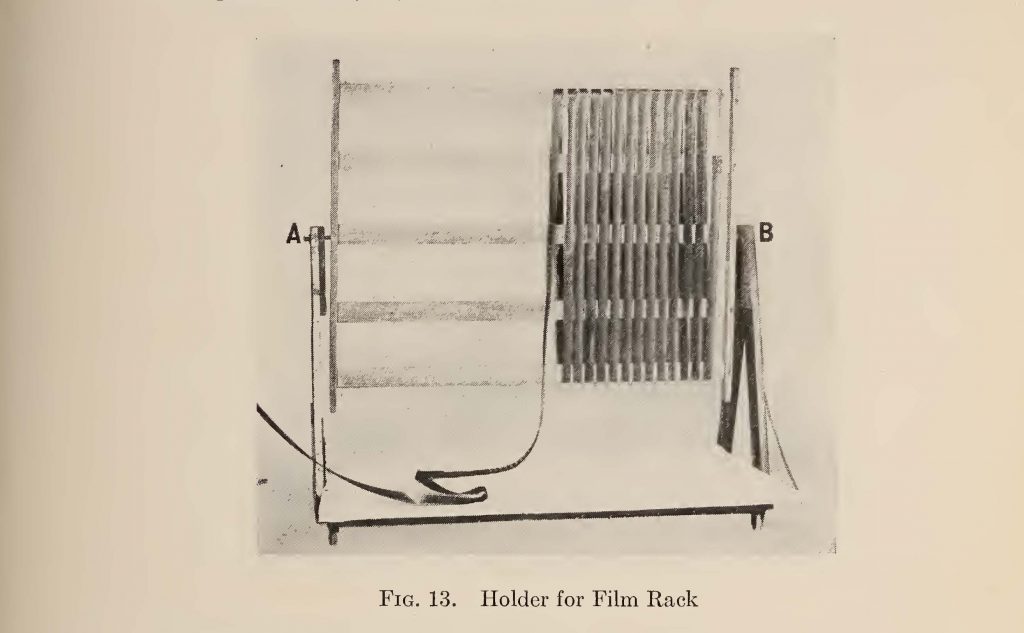

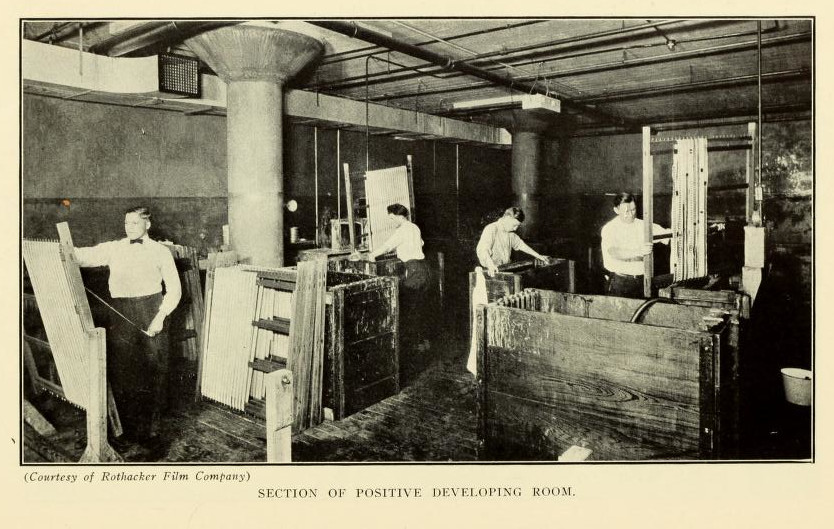

Another visual quality characteristic of the silent era you might notice is a pulsating in the image. The blacks do not stay at a constant level, but in a continual, subtle fluctuation. For most of the silent era, motion picture film, camera negative as well as positive prints, were processed by hand via the rack and tank method. The film from the camera magazine (which in the silent era topped out at 400ft) was wound around a rack, and processed in large tanks. In film processing, agitation (basically moving the chemistry around in the tank) is necessary as the chemistry that is in contact with the film will quickly exhaust as it works upon the film emulsion. Agitation was achieved by raising and lowering the rack in and out of the tank. Once the film was developed, fixed, and washed; it was transferred to the drying room and run onto on open drum.

This image fluctuation has two causes as identified by laboratory technicians of the era. One is rack marks. Due to the way the developer circulates within the tank during agitation, the tops and bottoms of the wind received more intense agitation in the developer than the sides of the winds, hence getting increased development. These sections of increased development would then print lighter than the parts with less development. The effect is compounded when prints are also processed by rack and tank.

The second cause was found to be that exhausted developer weighed slightly more than fresher developer, and in the tall tanks in between agitation, the developer would separate out, with the fresh developer at the top of the tank, and the more exhausted developer toward the bottom of the tank. This situation also effected the density of the resulting image in gradation from top to bottom of the tank. The result on screen from this, and rack marks, is a fluctuation in the density of the image. The effects of these quirks of rack and tank processing could be lessened depending on certain factors as agitation pattern and timing and strength and/or formulation of the developer.

These effects could be very subtle. The work of the laboratory at Universal was excellent, and the quality of their work was quite even. A small, independent studio like the short-lived Pioneer, not having the resources to maintain their own lab, would have to send their processing to an independent lab, and to cut cost, settle for one that produced lesser quality. Notice the extremity in the instability of the blacks in the 3rd example in the video below:

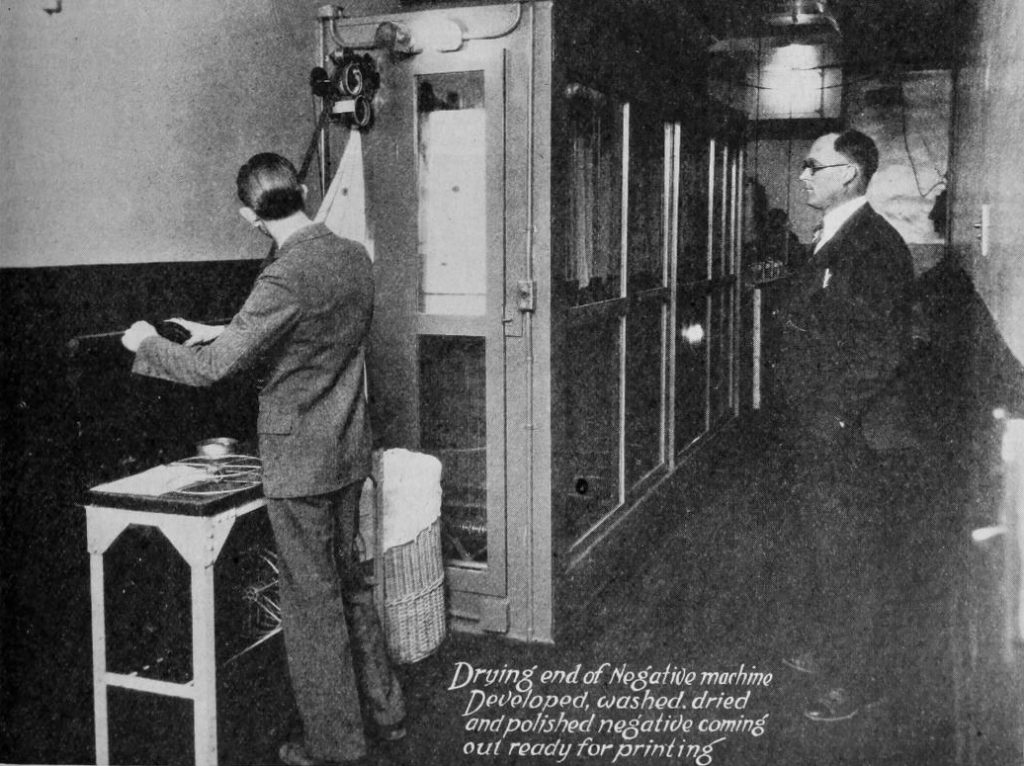

While machine processing of positives was not uncommon by the mid 1920s, it would not be until late 1927 that Universal would be the first in Hollywood to install a machine for processing of negative. American Cinematographer and Notes from the internal SMPE meetings would make note of their super-production THE MAN WHO LAUGHS, being the first Hollywood feature to have its negative machine processed, and that there appeared to be no compromise in quality.

There were multiple reasons why hand processing, despite its potential issues, remained in use for so long. One, was because the cost of a film and its potential to earn that money back, was tied up in the negative, it was considered a risk to trust its processing to a machine, which could potentially malfunction, and damage or destroy the negative, as opposed to processing by a well trained technician. Universal’s new machine had been extensively tested, and had built in fail safes in the case of loss of power, in that of a backup generator, or the ability to power by hand when absolutely necessary. In machine processing there was no handling of the film in-between stages. The film went in one end as exposed film stock, and came out the other as processed negative, dried, dust free, and ready for printing.

Another major reason hand processing persisted was due to orthochromatic film and its insensitivity to red, it could be inspected during processing in red light (much B&W photographic paper is orthochromatic, which is why it can be viewed under a red safelight while processing). The light meter would not be in regular use until the introduction of the Weston Meter in 1932, so exposure was often the estimation of a skilled cinematographer. The ability to inspect was greater assurance that the shot came out as intended. And the switch to panchromatic stock from orthochromatic meant inspection during processing was no longer possible. The irregularities of hand processing were an even greater problem for optical soundtracks, so sound hastened the adaptation of machine processing across the board.

shooting and projection speed

Taking us away from the image, to the presentation of it, brings us to the subject of speed. Throughout the silent era, cameras were almost universally driven by hand. Projectors, began as hand driven as well, but were eventually outfitted with adjustable motors. While it depends on the production, and the era of the production, it was generally a convention of the silent era that films would be projected at least slightly faster than they were shot, which was generally around 16 frames (or two turns of the camera crank) per second.

But earlier on, there was an expectation on the part of the filmmakers that their films, particularly dramas, would be projected back closer to the speed at which they were shot. For instance, Albert Capellani’s production of Camille for World Pictures, shot at the end of 1915 and released early in 1916, had its music cue sheet published in Moving Picture World. It gives a length of 5300ft, and a running time of 80.5 minutes, which works out to 17.5 frames per second. This cue sheet is unusual in that it gives a footage count (instead of the then standard reel count) and running time, allowing for a precise calculation.

Alas, there was nothing to make exhibitors to run any film at a given speed, and exhibitors were often inclined to run films faster to fit in an extra show per day. While this would cause some cameramen to shoot slightly faster, as late as 1925 the consensus of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers was that 16fps was a perfectly acceptable shooting speed, and registered fine projected up to 21fps. Shooting faster than this was seen to be a waste of resources as it would mean extra film stock in shooting and in prints, and increased use of electricity for lighting interior scenes to compensate for the shorter exposure time for each frame. Exhibitors simply needed to be made to stop overspeeding films. This however proved impossible to enforce.

Filmmakers found ways to combat the practice of overspeeding, gradually increasing shooting speed slightly as years progressed, and in front of the camera, actors slowing down their movements in performance, as was noted by Milton Sills (who appears in the clip of Miss Lulu Bett above, when interviewed for the 1929 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica on Screen Acting. (A factoid shared by Richard Koszarski to Ben Model, which he shared on his blog: https://silentfilmmusic.com/lsf50-deliberate-tempo-milton-sills/.) Sills’ comments were:

“While the normal speed of the camera in filming a performance is 16 pictures a second, or 60ft. of film per minute, when the picture is projected in a theatre, it is the custom to run it at the rate of 24 pictures per second, or 90ft. per minute. This, together with the fact that the film does not record movement as adequately as the eye, makes it necessary for the actor to adopt a more deliberate tempo than that of the stage or of real life. He must learn to time his action in accordance with the requirements of the camera, making it neither too fast nor too slow – a process of education only to be acquired through experience in the studio. The first mark of a novice is the rapidity and jerkiness of his movements, registered upon the screen as blurred and meaningless streaks. Another essential feature of the screen actor’s technique is a careful spacing of significant items which constitute the sequence of the scene. One thing and one thing only must be done at a time, and this in a clean-cut and distinct style with no distracting, irrelevant or unnecessary movements.”

And it can generally be said, that regardless of shooting speed most films from the mid 20s through the end of the era were intended to be shown around 24fps. And while some films were shot closer to this speed, many were still shot around 16-18fps, but designed to play faster, through their editing and performance.

Movements of the actors often have a snap and grace they would not have if run exactly at the speed taken. This is especially evident in the slapstick comedy, where projecting much faster than shot is essential to the gags. Much more can be said on this subject as well, but for an expert rundown of the use of under cranking in silent comedy, I will refer you to videos by producer and silent film accompanist Ben Model:

In not quite conclusion

We have now covered what I believe are some of the fundamental features inherent to image in films from the silent era. I think one way you can characterize these features, is as expressive artifice over verisimilitude, especially in the use of color and flexibility of shooting speed. Orthochromatic film and hand processing, amidst other things yet mentioned, were seen by some, particularly the film technicians, as flaws to be improved or corrected. Technically they are, if your goal is to create something that looks and sounds exactly like life. Orthochromatic film does not record tonal relationships realistically, but when you know how to use it, it’s imagery can be uniquely striking. That’s why it is still made for pictoral use for still photography. The irregularities of hand processing can keep the viewer more actively cognizant that they are watching a series of photographic images, which is only bad if that is something you want the audience to forget. But but like the random array of film grain, constantly changing from frame to frame, that forms the image, hand processing also imbues the motion picture image with an inherent vitality and movement — something that could be seen to be lacking in the perfectly regular, grainless video image of the digital pixel array.

Thank you for reading to the end. The next and final installment will be about the challenges of film preservation and how those affect the visual aesthetics of these films.