Hello, you don’t know me, but I want to talk to you about silent film. For my credentials: I am a graduate of the L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation at the George Eastman Museum. Beyond that, I have studied film and film history independently since my early teens. And, as an awkward, lonely teen, I used to skip school to watch movies on AMC (back when they showed old movies). In fact, I skipped no less than 6 times just to watch Julien Duvivier’s Lydia (1941) with Merle Oberon. Since then, I have read, watched, and discussed film with many willing and sometimes unwilling parties. My credentials are not as impressive as some people certainly, but hopefully you can appreciate my interest in film is more than casual.

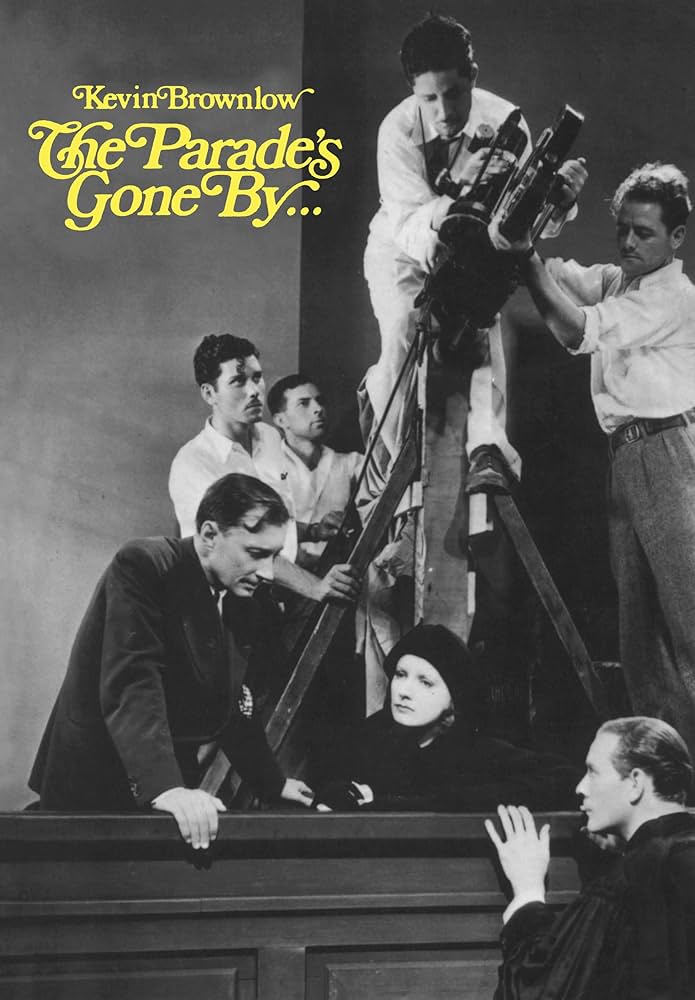

When I began studying film, I tried to see anything I had read was supposed to be great. However my circle of interest eventually grew smaller, until my primary interest was silent film. What drew me to it, I think, was the sense of mystery and romance that hung over them for me in the 1990s: their unavailability, their lot of being abandoned, misrepresented, and misunderstood. At first it was easier for me to read about them than it was to see them. And I read certain silent film tomes many times over in library copies: The Parade’s Gone By and others by Kevin Brownlow, American Silent Film by William K. Everson, and Seductive Cinema by James Card. It was through the same library where I found these books that I started to see a trickle of silents from their media collection. Fortunately, as the 1990s pushed onward, there came to be a greater number and variety of silent films issued on video, and the more I saw, the more I found that silent films move me in a way that most sound films do not.

Now why am I telling you all this? Well, film is a passion that is meant to be shared. I want to play a part in fostering a greater appreciation of silent film in a way that is accessible. I feel that appreciation of silent films tends to be somewhat insular. While I know that there is plenty of silent film scholarship in the present day, I doubt how much of that has made it into the mainstream of how film history is taught. And while any lover of silent film will tell you that silent film and dialog film are very different art forms, silent film is still often treated, in popular discussion as well as in film academia, as an historical stepping stone to ‘real’ movies.

In college film classes, the silents that are praised and discussed, tend to be ones lauded for their technique rather than their dramatic or expressive qualities. For example, any film theory class will spend plenty of time on Sergei Eisenstein, whose films from the start were appreciated outside of the Soviet Union on account of their technique, all but ignoring their propagandistic content. And in my acquaintance with film theory, I have encountered no one to look at the various modes of silent film to examine how they function, on their own or in relation to the dialog film. The changes in common film technique are regarded as progress, like the development of the automobile, the construction of which has gradually increased in efficiency and safety for the user. But works of art are not utilitarian objects meant to perform a task, they are, generally, meant to convey something of the human experience. And I do not believe there is one most efficient way to convey the human experience. Just as there is not one correct way to paint or draw images, create theater, write prose, or make music, there is not one correct way to make films. And just as we do not judge art from earlier eras as deficient for lacking the techniques employed in later eras or the present day, we should assess all films in the same way: according to their own merits.

That being said, silent film, more broadly speaking, also does not end with the silent era. You have the American avant garde, with the likes of Maya Deren and Kenneth Anger, films made exclusively outside the studio production system by artists trained outside of commercial cinema, are almost never dialog driven, or even make use of live sound.

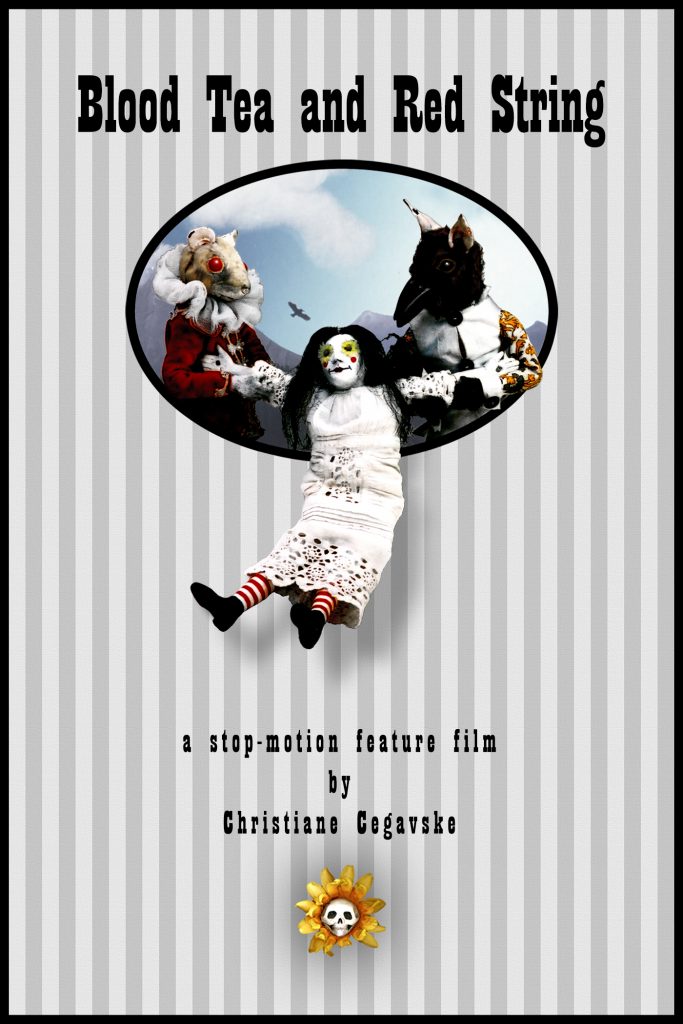

There is also an on-going tradition of wordless animation. Tom and Jerry and the Roadrunner cartoons can be included in this. Despite the talking lower half of a housemaid in Tom and Jerry, the shorts are driven by action and images, not dialog, as it has been noted, the classic cartoons of the 1930s, 40s, and 50s owe much of their form to silent slapstick comedy. Notable creators in the form include (though are not limited to) Tezuka Osamu, Jan Svankmajer, Christiane Cegavske. And even Pixar has dabbled with the prologue to Up and the entire first act of WALL-E.

You also have the music video. While the content can vary, many contain a visual narrative only loosely related to the lyrics, or might be a series of evocative images on a theme. And even if the lyrics are mimed, you are hardly left with the impression that the song is being sung live. Regard some examples from Kate Bush, Bronski Beat, or Beyoncé.

More humble is the home movie. The introduction of smaller gauge formats using non-flammable film brought movie making to the amateur as early as the 1912 with the Pathé KOK 28mm format, later to be followed Pathé Baby 9.5mm in 1922, by Kodak’s 16mm format in 1923, and 8mm in 1932. For all but the wealthy cinema enthusiast, home movies would be silent until the introduction of sound Super 8 in 1973, later to be replaced by the video camcorder.

There is also what I like to refer to as films that are silent adjacent. These are films that contain dialog, but the narrative is carried by the visuals. Such films often contain lengthy scenes with no dialog, and may have prominent music scores which demand attention instead of residing meekly in the background. A director who has many works that fall into this category is Mario Bava, whose career in Italian cinema as a cinematographer and director spanned over forty years from the late 1930s to his death in 1980. He learned his trade from father Eugenio Bava, sculptor, cinematographer and special effects technician, whose most notable credit is probably working on the 1914 spectacle Cabiria. Junior Bava became known for the pictoral beauty of his images, and within the industry, his ability to make cheap films look expensive (as most Italian post-war films were low budget by comparison to Hollywood), with lush lighting and composition, and a mastery of matte paintings. Many of his films open with lengthy dialog free openings with scenes such as this…

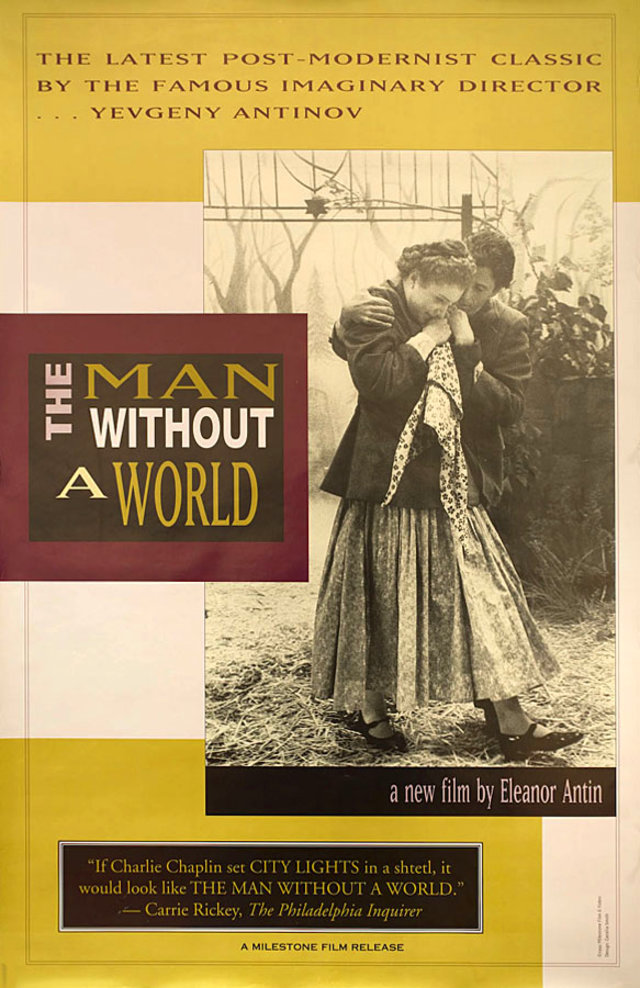

And most noticeably, you have the people who have self-consciously returned to the form of silent film just as it was left when the era ended, usually as homage or with the intention of evoking the past. The Artist (2011) being the most lauded of these efforts, though not the only one. Performance artist Eleanor Antin created a body of work in film, entirely within the mode of silent film. And one off independent productions like Blancanieves (2012) and The Call of Cthulu (2005) are more common than you might think.

Now my point of all this is: that silent film, defined broadly to mean films largely absent of and not carried by spoken dialog, has never truly ceased to be made. It is a tradition that has continued in spite of the predominance of dialog driven media. Now, why do I care and why should you? Well, of course the truth is you don’t have to, but I can honestly say that films that are silent, or at least silent adjacent, often reach me in a way that dialog based films do not and I don’t think I am alone in this.

It is often said by admirers of silent film that they require more active participation than dialog films. Like reading a book, you must give it 100% of your attention. The audience has grown accustomed to taking in a movie or TV show while performing other tasks, dividing their attention among several things, especially now; our phones. (There are now such concepts as ambient television and second screen content.) You are carried by the dialog, and glance at the screen intermittently, giving it more or less attention as your interest demands. The motion pictures become part of the noise of daily life, along with the piped in music in stores and restaurants that is so ubiquitous, you hardly notice it. You know it’s there, but you’re not listening. Its absence can be more noticeable than its presence as we expect a certain base level of stimulation at all times.

I have heard silent film called an acquired taste. And this is true. It’s true of almost anything you are not accustomed to. To an American youth, whose musical landscape is almost exclusively R&B and hip hop influenced popular song, an older form such as the Western opera is likely to be just as unfamiliar to the ear as the Chinese opera. While unfamiliarity is an obstacle, broadening our cultural horizons can be infinitely rewarding, to new experiences and new points of view.

Silent film, to those open to it, can offer unique rewards. Words have a concreteness. And when the spoken word is given primacy, the eye can grow lazy. Hanging your attention on the concreteness of the words, can dull you to the nuance of things that require interpretation. When silent film strips away the spoken word, the viewer grows to be attuned to interpreting image, gesture, expression, and interaction – they meet a work halfway, engaging with it, rather than passively experiencing it. The viewing of silent film is often meditative rather than merely stimulating. Meditation often prompts reflection, rather than reaction. Modern life is full of stimulation, reaction, and a lack of nuance.

The gift of the art of silent film, and of most good art in general, is a respite from noise, to engage rather than distract, to provoke thought and emotion, rather than to numb. Now, it’s not my intention to say that dialog films are inferior works to silent films. And I don’t mean to say that words and the spoken word are not capable of great power. But for me, there is an elemental quality to the mute image, whether drawings, paintings, sculpture, photographs, stained glass windows, or silent cinema. It is something that bypasses words and logic, to a certain universal sense of beauty and connection.

Does this make sense to you? I hope so. But if it doesn’t, that’s fine too. Perhaps it is the concreteness of words and the beauty of their usage which fills you with awe. I have a friend, a great lover of books, with a certain degree of face blindness who admits most silent films are not for him, because he has a hard time telling who is who, and reading body language is also not his greatest skill. I have no intention of pushing silent film as an elitist, aesthetic snobbery for which being a devotee marks one as having taste and sophistication. Nor is there an underlying message of “we need to go back to the old ways because the old ways were better,” as I am not necessarily talking about very old films. Though I will qualify this by saying, to me, a film ten to twenty five years old is “newer,” whereas I know most people would consider that older. I only recently saw Lars and the Real Girl (2007), and had the impression I was watching and enjoying a newer movie, only to realize it’s over fifteen years old.

But in starting this blog, I hope to reach and amuse those already interested in the silents, but perhaps looking for some deep dives and new perspectives. I also hope to reach those more casually interested in film, art, and history. And if I can make a few converts out of those, I’ll be very happy. Lastly, I hope to reach some of the fledgling filmmakers out there. While works of silent film are still created here and there, there should be more. I believe the silent film is a form with great expressive possibilities, especially for the artist of today, with so many tools, film and digital, at our disposal. I think all we need is a bit of encouragement for a full scale revival. Of course it will never again be the primary mode of cinema. The dialog film is so instantly accessible for so many people. But it doesn’t need to be the primary mode. It can sit off to the side, cinema’s quieter sibling, who is happy to have a conversation with anyone who is willing to meet halfway.