Pardon for this not being the final installment on the basic aesthetics of the silent era, but I was buying a house and it closed about a month earlier than expected and I’ve been immersed in a move and haven’t had the patience for deciding on frames and clips. It’s already written though.

But I went to The Dryden Theatre at The George Eastman Museum to see Dolores Del Rio in one of her 1928 releases, Revenge. It was part of a series of screenings of films in their collection printed from the original negative. It’s about 3 1/2 hours round trip to Rochester for me, so I picked the silent in the program I had never seen. I had also never seen a Dolores Del Rio movie or one directed by Edwin Carewe, and I was glad to make their acquaintance, but the print was a disappointment, but more on that later.

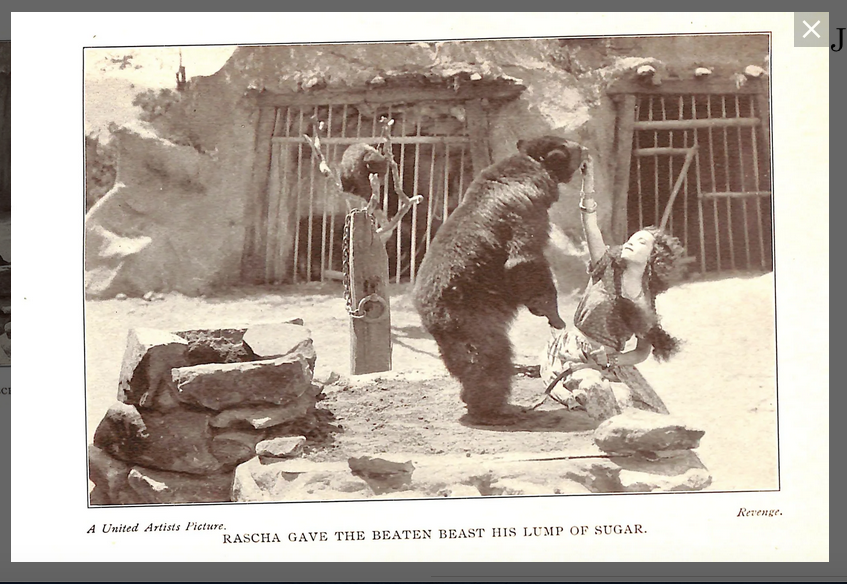

Based on a 1921 short story by Konrad Bercovici, The Bear-Tamer’s Daughter, it is one of three films produced under/released by United Artists in 1928-29 that include a scene the hero getting whipped by a woman. One is Von Stroheim’s Queen Kelly, another is Tempest with John Barrymore (Von had a hand in the screenplay), and I would bet somehow Von had a hand in this, if only perhaps suggesting to someone that the Bercovici story would make a good movie. The Bear-Tamer’s Daughter was anthologized in The Best Short Stories of 1921, and I managed to find the full text online, and while the film elaborates on the story to bring it to feature length, it is quite faithful to the text. I think it is also not a coincidence that Von Stroheim’s 1934 novel Paprika is similarly a tale of a beautiful, tempestuous gyspy woman.

The story is set in the mountains in Eastern Europe with a group of gypsies/Romani. Early on the film has a number of hyperbolic titles about their primitive passions, but, just as with Clara Bow’s character in Call Her Savage, Del Rio’s character Rascha also seems to be unique amongst her people in her savagery. Everyone else in her village seem pretty sane. The thing is, she tames bears with her father. A young man comes wooing, and she finds him tame and pathetic. He finds himself a nice girl, and Rascha is jealous. But she finds a healthy match in Jorga, the son of her father’s rival, who is also a bear tamer. While she gets in several lashes with her whip, he wrestles her to the ground and cuts off her braids. Rascha is humiliated, as it is a great shame among her people for a woman to have short hair. (The dynamics in this scene remind me a bit of the scene from Von’s Queen Kelly with the underpants.) While Jorga is openly smitten, Rascha retains a pretense of disgust. There is some cat and mouse action between the two. One night Rascha goes out in search of Jorga to seek her revenge, but he slips into her bedroom to sleep in her bed while she is out. Tensions mount when Jorga and his band crash a party. When Rascha’s short hair is exposed and all the women mock her, Jorga orders his men to cut the braids of all the women who have done so.

I won’t give the ending, but the basic plot is of a romantic comedy, but instead of laughs we get the erotic tension of something like The Flesh and the Devil with Garbo and Gilbert, with the comic book exoticism of The Sheik, but in Eastern Europe instead of the Middle East. While Del Rio’s co-star Leroy Mason was never a star, having a career mainly in B westerns, he matches her energy well.

Edwin Carewe’s production here is beautifully mounted. I’ll have to seek out Milestone Film and Video’s old DVD of his and Del Rio’s later collaboration Evangeline. (It’s now out of print.) And I think we’re all still hoping for a disc release of their Ramona from the same year. It’s restoration has had screenings, alas not with me in attendance.

Now on the Eastman Museum’s print. While I don’t doubt that it was printed from the negative as they say it was, the detail was there, but this was not a great illustration of the beauty of black and white cinematography in a black and white film print. If they had stopped the screening to tell us they had accidentally been screening a fine grain master positive, I would not have been surprised. Not that I think this happened, anyone who works at Eastman is going to know how to identify a fine grain over a projection print. But the tonal scale of this print ranged from dark grey to medium-light grey. In the interiors, sometimes less than that. The image was often so dark it strained my eyes. No deep blacks, no bright whites, and an odd color cast that gave the image a greenish brown appearance. It was a beautifully shot film lost in an ugly print.

I don’t know the history of this print, but a screening or two before in this series was Von Sternberg’s The Docks of New York, which I’m quite sure is a print dating from the 1950s which I believe James Card obtained from Paramount. Perhaps if this print of Revenge was made by United Artists at some point for the museum in the 1950s or 60s, the work was hastily done. If the original timing indications from the negative were lost, I doubt they were going to go through the trouble of retiming the entire film. (Timing/grading, if you don’t know is making decisions for each scene on how light or dark or contrasty to make the print, and of course in color, there are decisions made there too.)

I have seen the Museum’s print of Possessed (1931) with Joan Crawford and Clark Gable, which was also printed from the original negative, and it’s gorgeous. This I know was printed at the Cinema Arts film laboratory in Pennsylvania, which does exacting work. The roundabout point being, that even if a print is made from the original negative, the lab work still needs to be good to have a good print.

Back to Revenge, it’s the sort of film that will likely inspire titters in a jaded modern viewer who considers themselves to be very sophisticated. But to this viewer, exhausted with the modern, app driven dating scene, which often has the sterility of a corporate interview, the passion on display here is something to aspire to – to some degree anyway. But I don’t recommend whipping someone without their consent.