In the previous two posts we looked at what I consider to be some of the basic components of the visual aesthetics of films from the silent era: the use of orthochromatic film, their use of color, the artifacts of rack and tank processing, and the flexibility of shooting and projection speed. But the way silent films appear today is often very different from the way they looked to audiences on their original release. But before we go on, we will digress for a moment to explain:

the nomenclature of motion picture materials

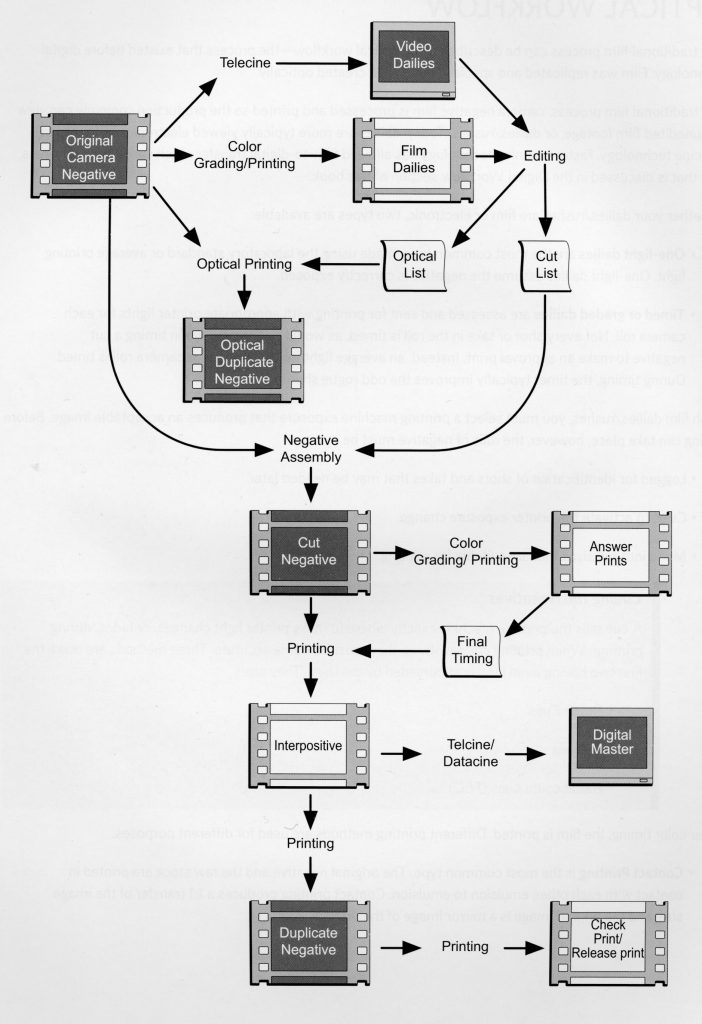

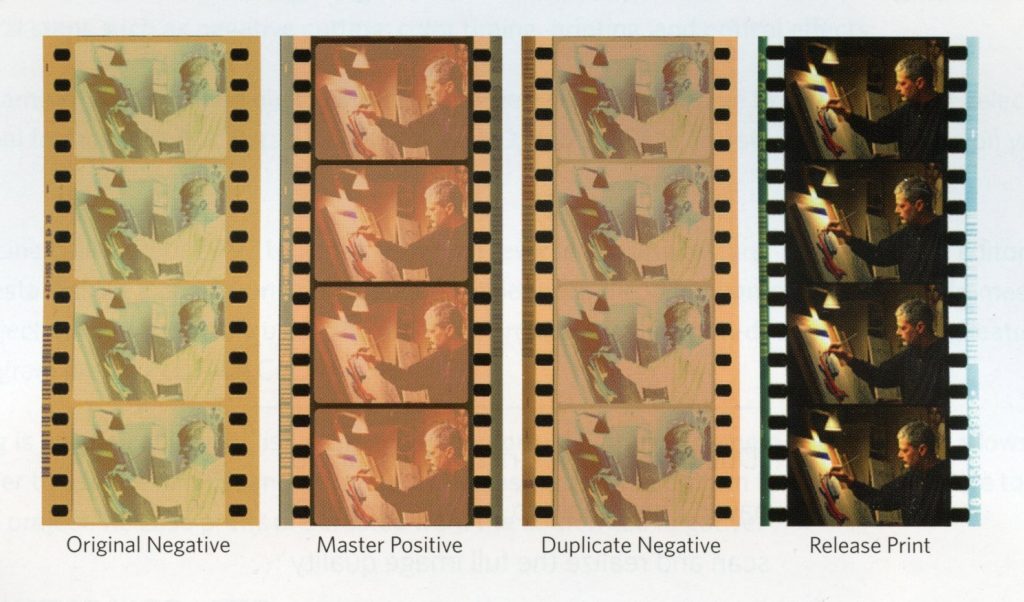

When studio productions are shot on film, the film that passes through the camera is called the original camera negative, from this you can make a normal contrast print for projection, or you can make a low contrast positive print. This low contrast positive is a secondary master from which you can make another negative, called a dupe or inter-negative. The camera negative is first generation, a positive made from the original negative is 2nd generation, a negative made from that first positive is 3nd generation, a positive made from the inter-negative would be 4th generation. The original camera negative, master positive, and first internegative will serve as a studio’s master materials, ideally stored in different locations, so if something happens to one, you still have a high quality master of the film, though sourcing the original negative is always preferable, since it yields the highest quality. Unlike digital files, which can be copied endlessly with no loss in quality, analog materials like film and tape, lose quality with each successive copy of a copy. The quality of duplicated analog materials is also highly dependent on the equipment used for the duplicating, the condition of the materials being copied, and the skill with which that equipment is utilized. (Images from Kodak’s The Essential Reference Guide for Filmmakers, pgs. 160&165)

In the last decades of the theatrical presentation of 35mm prints before digital projection took over, you would make a number of internegatives from the master positive in order to have a run of sometimes thousands of prints so that the same movie could open on the same day in thousands of theaters. Making prints from dupe negatives ensures you have minimal wear and tear on the original negative and master positive, though this comes with a loss of image quality. When a film’s run is over, all the release prints are generally destroyed and the material recycled. The original negative, master positive, and other master materials are kept in the vault for access, when needed for video mastering, theatrical re-release, or whatnot.

film materials in the nitrate era

In the silent era, and for some time afterward, the release prints shown in theaters were printed directly from the original negative. While this put more wear on the original negative, studios were not thinking long term in regards to their film materials. The objective was the best quality print for its initial theatrical run, usually its ONLY theatrical run. Depending on the film, it might have less than fifty prints made for release, or at maximum a few hundred. In the feature film era, film would open first in large cities, when the prints were pristine. After they had finished their run there – a few days, weeks, or even a few months or more, depending on how popular the film proved to be – the film prints would circulate in smaller cities, eventually working their way to small towns. At the end of their run, these prints, after much handling and projection wear, and cutting from different regional censors, would be returned to the studios where they would be destroyed. Though it happened that sometimes prints did not get returned at their end of their run, especially those that had made it to far flung places and where neither the studio nor the theater wanted to pay shipping back, and the prints would remain at their last stop. It is in these escapee prints which many silent films survive today.

The majority of older films from the sound era you see today, whether we’re talking about 1936 or 1996, and whether on an old commercial VHS tape or from a streaming platform, are generally a fair representation of the film audiences saw in its original release, within the limitations of a home video format. The video transfer or scan of the film was most likely made from a clean, complete master source held by the studio, whether an internegative, master positive, or even the original negative that passed through the camera.

The master materials of studio films made in the sound era, 1929 up to post WWII, were lucky in that they didn’t have long to wait until they got a second life being screened on television. The old films suddenly had commercial value via licensing fees, and so were worth maintaining.

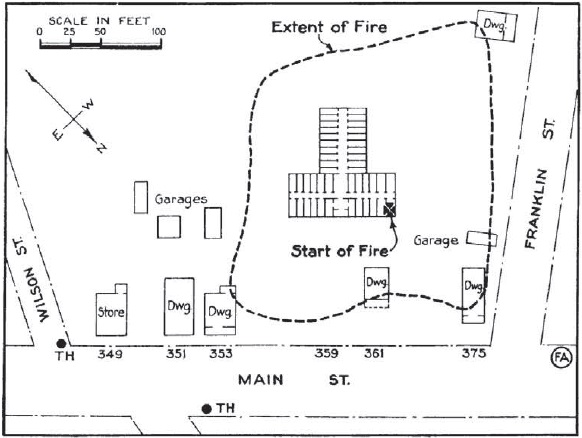

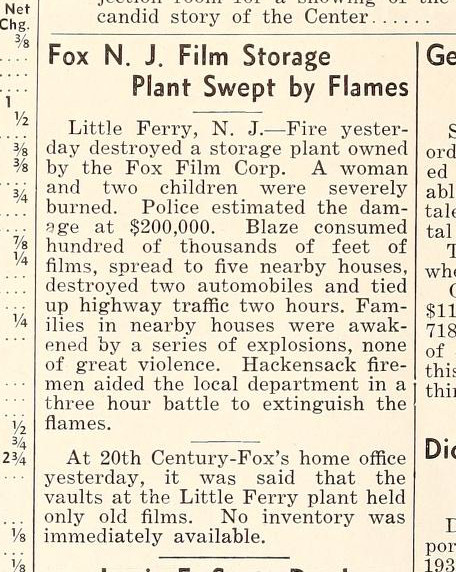

In general, studios did not take care for, or sometimes even bother to keep the master materials of their silent films after a certain point. Old films were occasionally reissued during the silent era, but after the advent of sound, they were seen as worthless, aesthetically and commercially. The nitrate film stock in use by the motion picture industry until 1950, was highly flammable, and there were many vault fires in the studios earlier years. These generally were a result of the highly flammable film being stored uncooled and unventilated in the midst of a summer heat wave, resulting in the film self-igniting. In 1937, Fox would lose most of their pre-1935 master materials in such a fire, and Universal would lose much of their silent master materials in smaller vault fires over the years, until making the decision to dispose of everything left that did not have a soundtrack in 1948. And even when it did not catch fire or get thrown out, there is also the spectre of nitrate decomposition, the breaking down of the film base which carries the image. Decomposition is accelerated when film materials are not kept cold and dry.

what survives, and the challenges of preservation

In 2013, David Pierce at the Library of Congress, in cooperation with FIAF published a study of the survival rate of feature length films made in the US during the silent era, from 1912-1929. The rough rundown of statistics is that of the roughly 11 thousand features produced, 70% have no known surviving copies. 14% survive in 35mm prints of their domestic version. 11% survive in either a foreign release print (which could differ from the domestic version), or in a substandard gauge like 16mm, necessitating a loss in quality. 5% survive incomplete either in an intentionally shortened version, or as is often the case, one or more of the reels has gone missing or decomposed, or someone at some point excised a scene to save for one reason or another, and only this has survived. For example, a few years ago the Cineteca Espanole found two minutes of random shots of Theda Bara from her 1918 spectacle Salome.

And again this study was on the survival of feature films, this does not take into account short films, fiction and non-fiction, which account for almost all the production pre-1912, and a substantial amount of production afterward.

And among those films that survive in 35mm, more or less complete, in their domestic versions, a large portion survive in the form of release prints that for one reason or another, were not returned to the studio at the end of their run. When the value of silent film began to be reassessed in the 1950s and 60s, these original release prints, often worn, damaged, and censored were sometimes all film preservationists had to work from. Dupe negatives were made from these. But release prints were never meant to be used as master material. Due to the higher contrast of positives made for projection, as opposed to a low contrast master positive, unless the utmost care is taken in photochemical duplication, you can easily lose the detail in the highlights and shadows. And in the early days of preservation, the printing equipment was also not made to deal with often shrunken and warped older film. Sometimes, resulting copies were a pale shadow of the originals, lacking the sharpness and clarity of the original prints. Color, in the form of tinting, toning, hand coloring, Technicolor sequences and other processes common throughout the silent era, were not recorded in a black and white dupe negative, and if notes or references were not made, and they generally weren’t, the original color effects cannot be replicated in new prints. In the early days of film preservation, it was often standard practice to dispose of the flammable nitrate originals once a dupe negative was made, so you could no longer go back to the original for reference or to perform a new preservation as techniques improved. Fortunately some films survive in beautiful original materials still, and are afforded meticulous restorations in the digital realm, where physical damage to the image can be addressed in ways that are impossible by traditional photochemical means. Many of the restorations of the past twenty years really do represent these films as originally seen, or as close as can be approximated. But a great many films of the silent era, only survive in versions that are heavily compromised.

films can survive complete and in 35mm, but still look nothing like they did in their original release

As mentioned earlier, there are films which only survive in substandard formats such as 16mm, super 8 and 8mm, or if you’re in Europe, 9.5mm, along with other less widely used formats like 28mm and 17.5mm. With these it is to be expected there will be some loss of quality. With quality lab work though, 16mm can still retain much of the quality of the 35mm. I have seen stunning original 16mm prints made for Kodak’s Kodascope film rental library in the 1920s and 30s. Though these tend to be more the exceptions. Even the more typical quality of 16mm sometimes can be made to look presentable with digital regrading. Universal also had a 16mm rental library of its films during the same period as the Kodascope Library, but their lab work was markedly inferior. However survival of a film in 35mm does not ensure a film survives in quality the represents how the film looked originally.

Film clips from Fraternity Mixup (1926), Lorna Doone (1922), La Llorona (1933), and White Tiger (1923) illustrating the variance in image quality of 16mm prints. Click the links for the DVD or Blu-Ray source.

A Fool There Was (1915) Theda Bara’s star making debut was preserved by the Museum of Modern Art when they began collecting films in the 1930s. The laboratory work in copying the film was exceptionally poor. Presented in the sample clips below is a standard def transfer of 16mm material, but I have seen MoMA’s 35mm projected, and can honestly say it does not look markedly better. The image is soft to the point of simply looking out of focus. (Sourced from the Kino Lorber DVD)

Our Dancing Daughters (1928) was Joan Crawford’s first star vehicle. Preserved over 30 years later than the Bara film in 1968 by MGM at the start of their move to preserve their back catalog, it is somewhat better, but suffers from the same problems of a very soft image, but also very little definition in the blacks. The body of the tuxedoed John Mack Brown in several scenes disappears into the background. All you see are his face, cuffs, and collar. The print is also seems to not have been cleaned prior to duplication. There is a lot of dirt throughout, and hairs get stuck in the gate for a number of scenes. Just recently, however, the film was given a digital restoration by Warners. The dirt and hairs are gone, the Movietone track is clearer, so it is much improved, but there is simply nothing that can be done about the lack of detail. Digital tools have been a godsend for repairing damage, but you can not restore what is no longer present in the image. I don’t even think AI could give John Mack Brown his body back. [Sourced from the Warner Archive DVD (unrestored) and Blu-Ray (restored)]

But then these two films also present different issues. Our Dancing Daughters, with its abundance of tight closeups and camera movement, can be seen to suffer less from its degraded surviving material, since editing and camera movement are cinematic features that are less impacted by image quality, and the close-ups bring the performances closer to the eye of the viewer. The film technique of A Fool There Was, being an earlier film, is based more around staging, lighting, and composition, with a camera that stays farther away from the actors. In a phenomenon I’m not quite sure how to explain, the farther a subject is from the camera, the more apparent fine detail tends to be lost in a poor copy. So to a greater extent in A Fool There Was, the film and its attributes are obscured.

In the above clips, I have also included for contrast clips from films whose preservation work gives a better impression of the original:

The John Collins/Viola Dana film Children of Eve was released the same year as A Fool There Was. This was preserved from the original negative by the Library of Congress, presumably in the 1970s. Surely you can see a world of difference between the quality of Fool and Eve, especially the closeups of their stars. But while this generally looks beautiful, the tinting scheme is not reproduced in the Blu-Ray from Kino Lorber, presumably lost.

Marion Davies’ original personal print of her 1926 vehicle Beverly of Graustark is held by The Library of Congress and is available on the Undercrank Productions Blu-Ray from a 2k scan from this print. As you saw, the images are sharp and clear, with detailed blacks and highlights, and sparkles in a way the Our Dancing Daughters can no longer.

Preservation under better circumstances

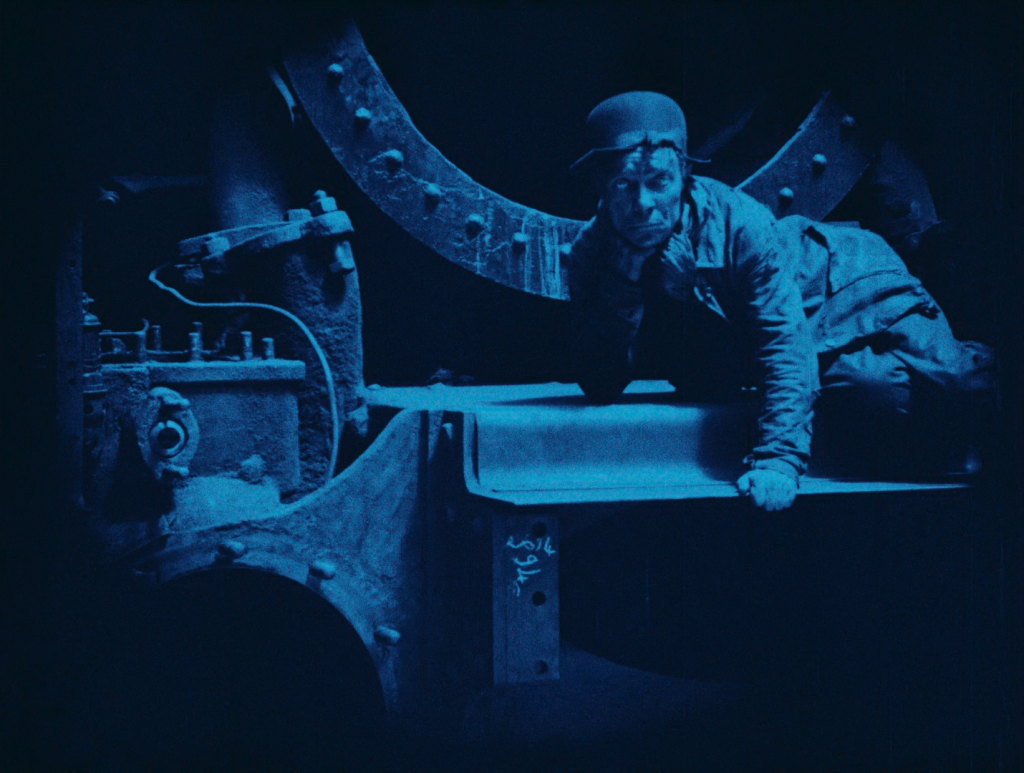

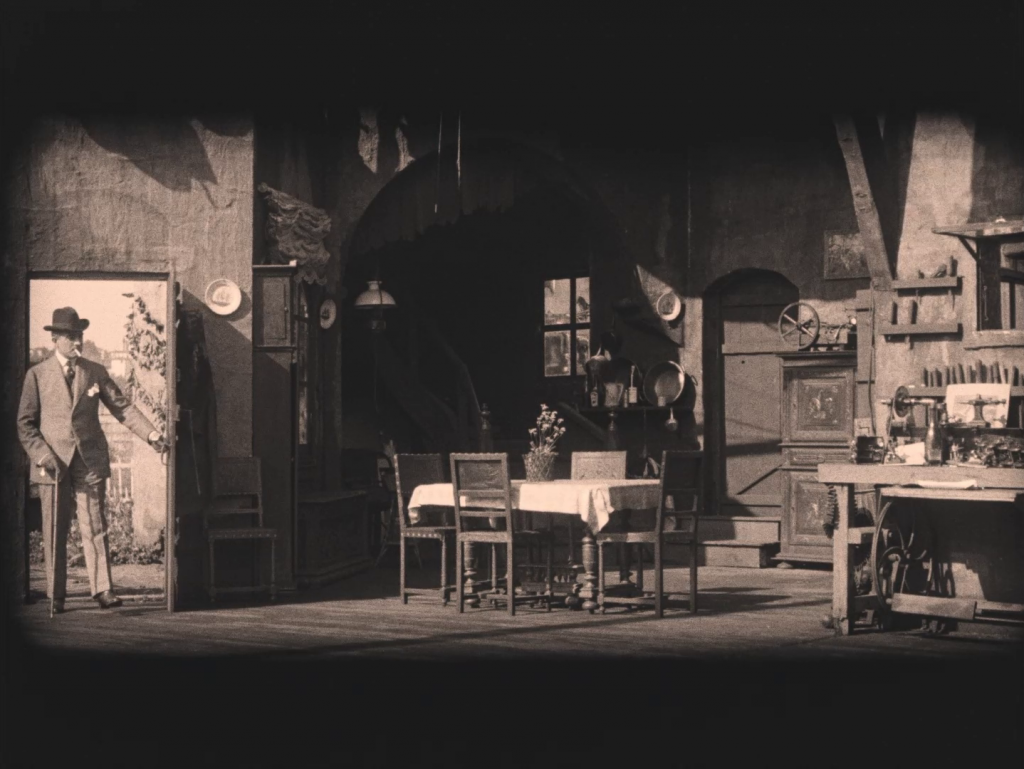

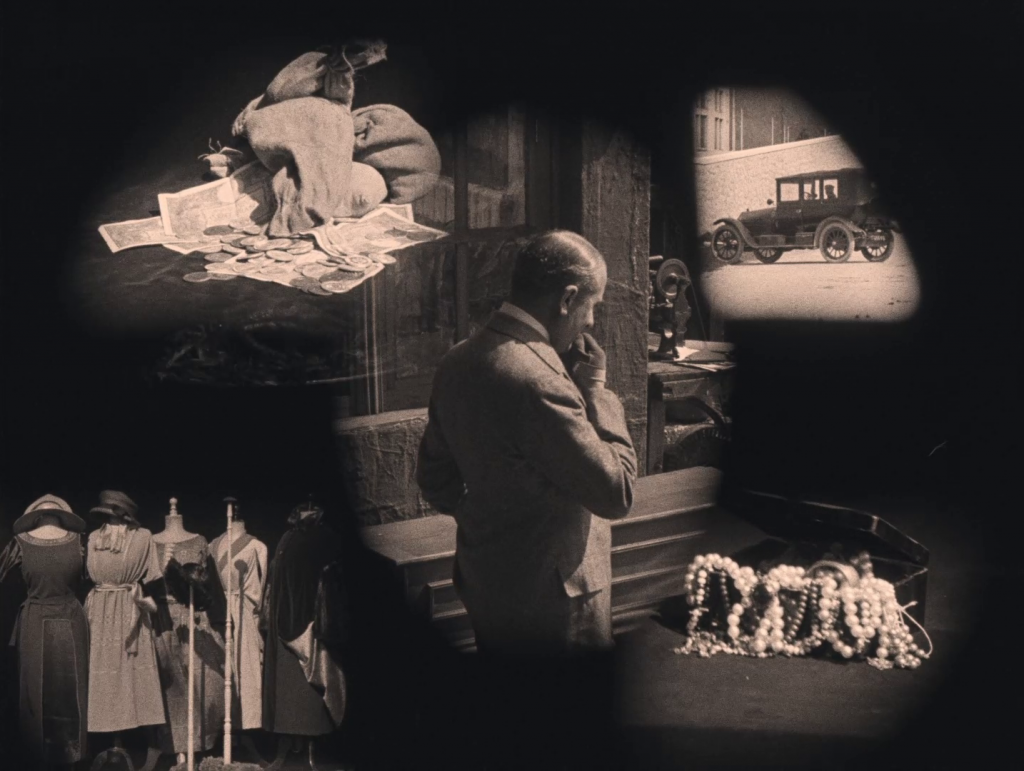

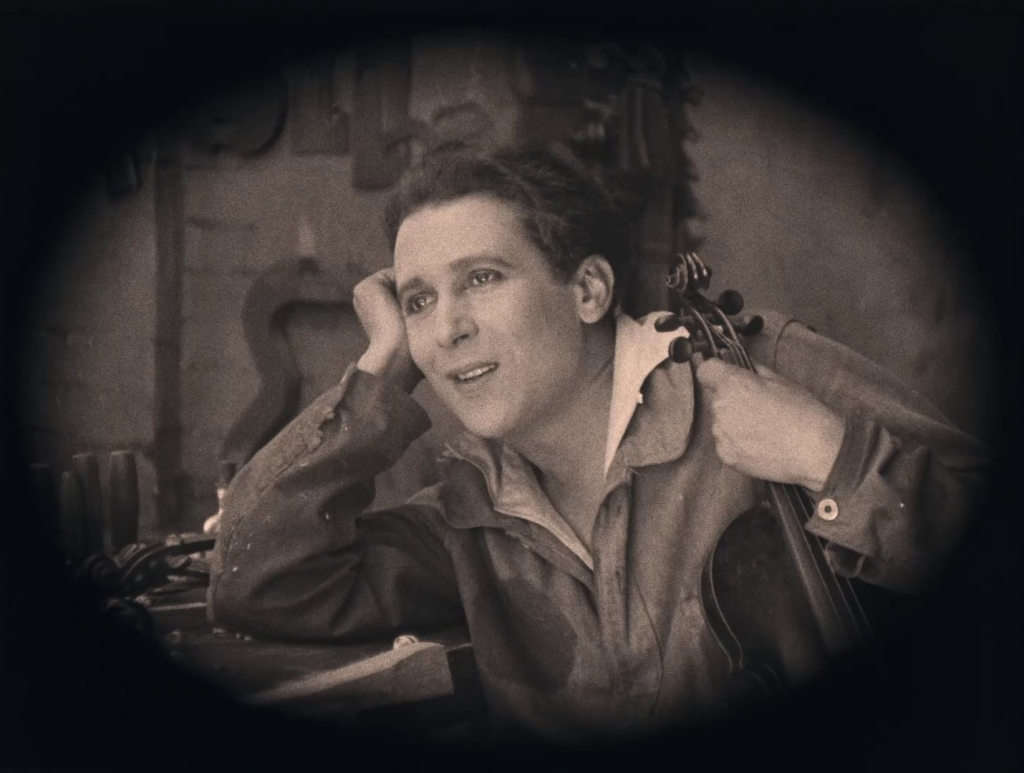

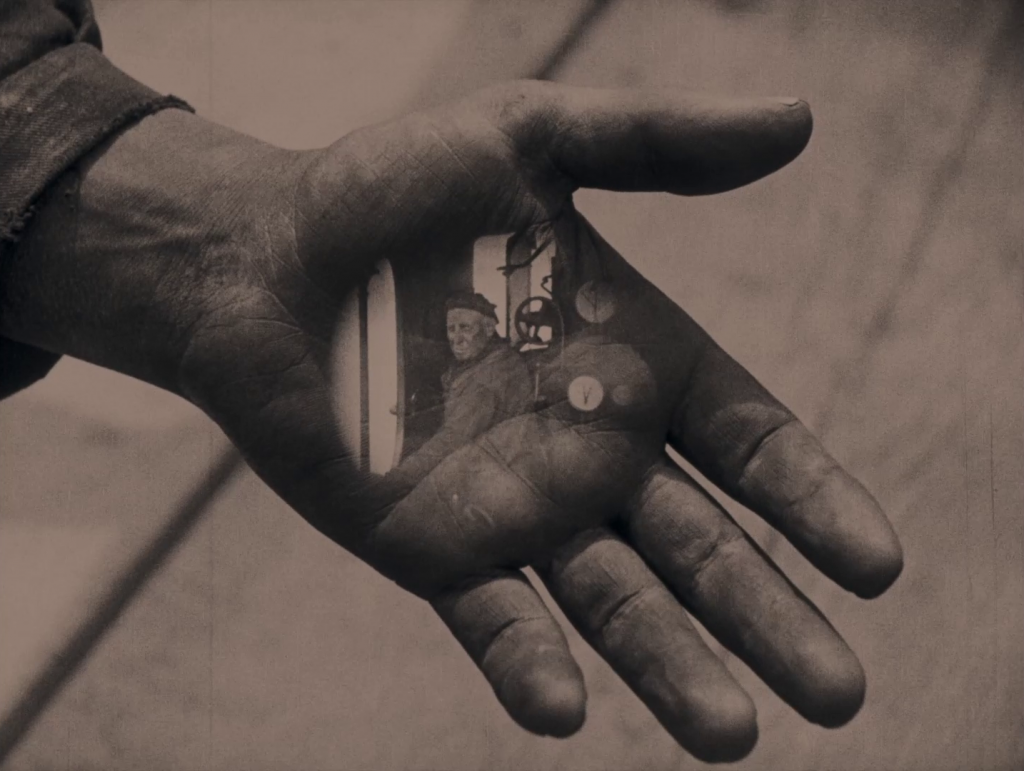

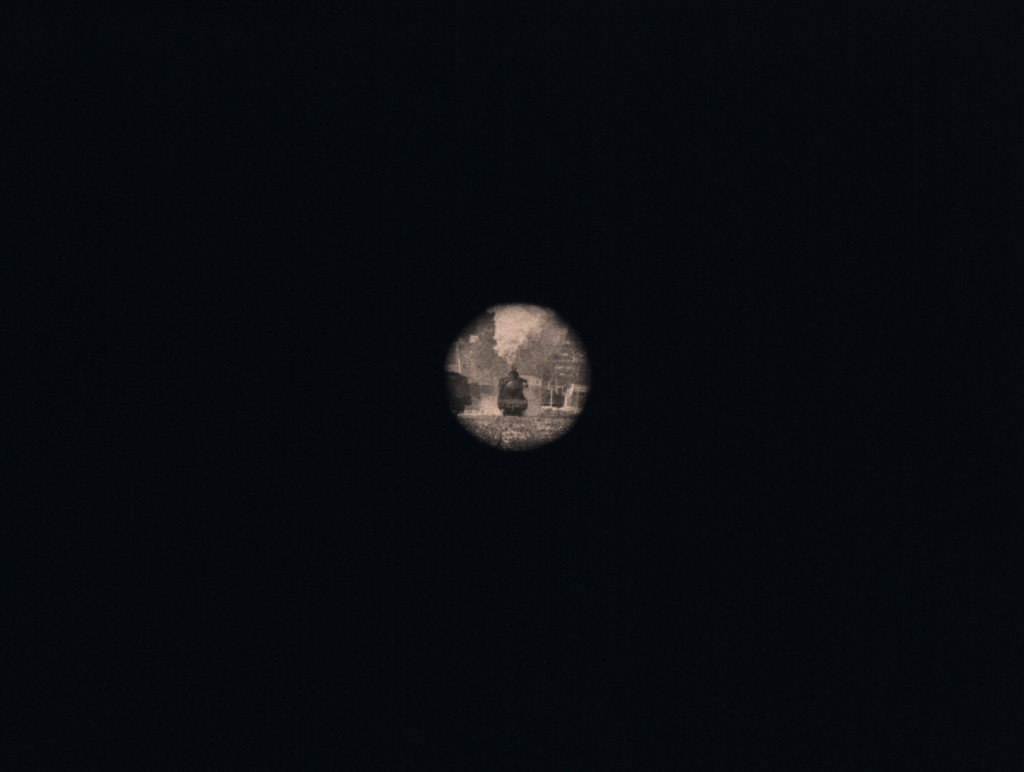

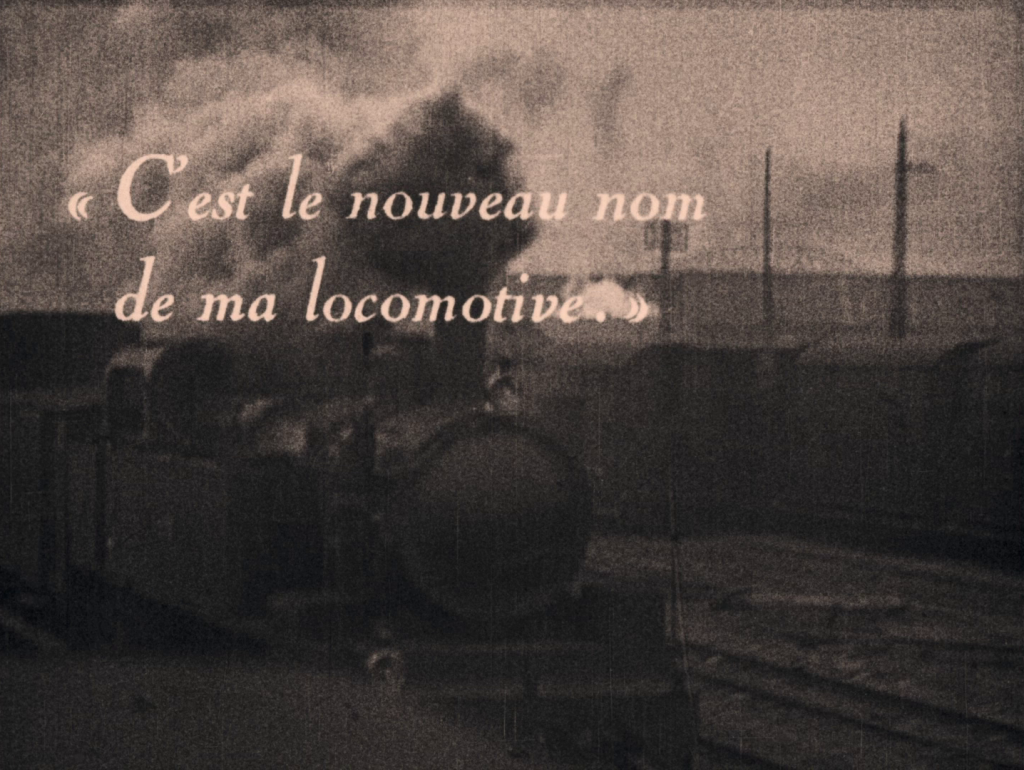

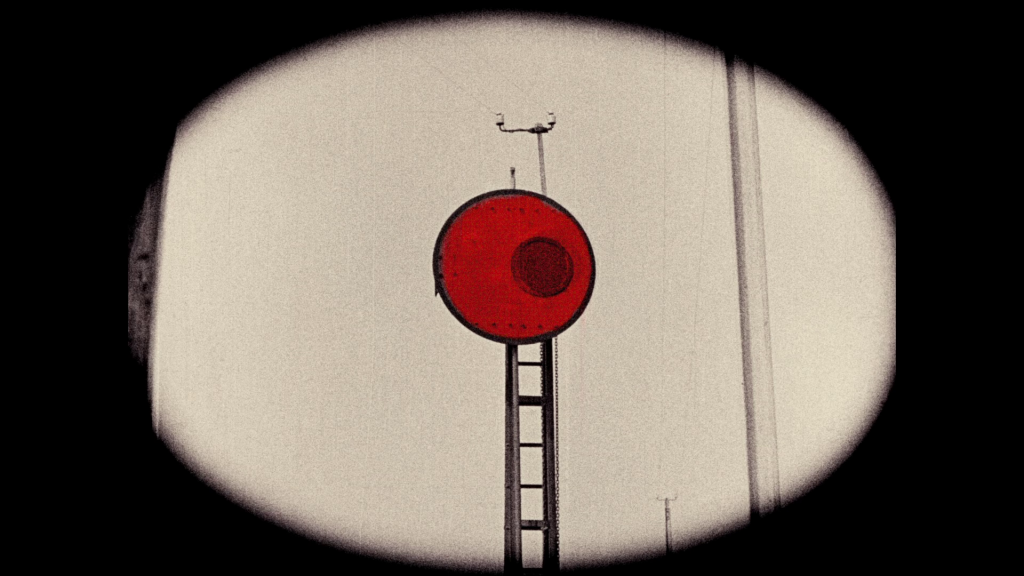

Sometimes preservation of a silent film is simple, like with Beverly of Graustark. The film survives in a pristine complete original print, and all that is necessary is duplicating it in a more stable, high quality format (35mm film or hi-res lossless digital), and conserving the original for future access. But the preservation and restoration of some films can be monumental tasks, and take years. Abel Gance’s La Roue, released in 1922 in various lengths, and was in recent years restored in conjunction with Pathé and the CNC to its original premiere length of 7 and 1/2 hours, from a mix of materials from various European archives, including much of the original negative. It is among many recent restorations that can be said to present the film as originally intended. Gance’s film can be seen as a compendium of the features of silent era filmmaking I have discussed (and a few others): orthochromatic imagery, in the way the film is shot and edited, its use of text as image, and its use of color in tinting, toning, and stencil color, all in service of a dramatic narrative. I tried posting a clip to YouTube, but it was blocked for copyright, so I have provided a gallery of images below:

orthochromatic imagery

(Of course, the whole film was shot orthochromatic, but it can be easier to appreciate without the heavier tinting. These images are not black and white, but have a light amber tint. The main body of the film employs this tint.)

tinting and toning

varying the size and shape of the image

text as image

applied color via stencil

On image quality and sound films

Now with a sound film, the sound is a substantial part of what makes the film, so if you were to have the image survive in compromised quality, especially in a production where the content of the screenplay is largely within the dialog and its delivery, you could lose some image quality without losing the essence of the film. Take for example, Bette Davis’ break out role in Of Human Bondage (1934). No master material survives, and for years it circulated mainly in 16mm prints and the video copies derived from them. They looked ok, but dupey, like this here. But I don’t think you can say this detracts from the power of Davis’ performance.

but silent film has only image

But in silent film, the image IS the film. To compromise the image is to lose the film’s content. While it might not be as obvious and quantifiable as losing a shot or a whole scene – a specific amount of footage from its running time – something still is irretrievably lost. You might think that it amounts to losing a mere surface prettiness, but you can only lose so much texture, detail, and definition before you have an image which can no longer communicate what was intended. To what extent have you seen F.W. Murnau’s famed Nosferatu (1922), if you have only seen it in one of MoMA’s 16mm circulating library prints, (as most people saw it in the latter half of the 20th century) instead of in the 2006 digital restoration by the Murnau Stiftung, whose primary element was the Cinematheque Française original tinted nitrate print? In the early scenes, the Stiftung restoration breathes with the atmosphere of springtime. Notice the shadows of the leaves on the trees can be seen shaking in the breeze. In the MoMA 16, the entire film from start to finish appears to have been bled of all life.

For an even more extreme example than the Nosferatu 16mm, one film I read about early in my and whose stills tantalized me was the fellow German Expressionist film Warning Shadows (1923). When I finally purchased a video cassette copy in the mid-1990s, I was aghast at the quality I saw. The image was so soft, and so dark it was unintelligible. Nevermind detail and texture, the action of the film barely registered. Several years later I found a 16mm print on eBay, and thought, “Yes! Finally I’ll be able to see it!” And was depressed to find it was a print of the same generation and quality as was used for the transfer of the videocassette I had purchased, and returned. The quality was not appreciably better having a 16mm source. It is at a point such as this when you have to ask yourself, if a print is of such poor photographic quality, how can I appreciate the craft of the cinematographer? If I cannot make out the sets, can I appreciate the craft of the art director? If the actors register as vague human shaped figures, and their faces as orbs with three black dots for eyes and a mouth, can I appreciate the craft of the actors? And if all of those things are compromised, can I appreciate the intentions of the director and screenwriter? It is at such a point when you have to admit that despite having seen the movie, you have not actually seen the movie. It would not be until 2005 when Kino Lorber would release a standard definition transfer on DVD from the 35mm preservation material that Warning Shadows could be seen in any appreciable quality in the US.

While I was eventually able to see Warning Shadows in a version I could appreciate, some films only survive in versions that the filmmakers themselves do not recognize. When a print of Karl Brown’s Stark Love (1927), shot on location in the Appalachian mountains, came to light in the late 1960s, David Shepard watched the resulting preservation with the director. He recalled later in a 15 Feb 2012 post on Nitrateville.com:

“I was at the AFI when the film was recovered from the Czech archive. It bore the title ‘In the Glens of California.’ We couldn’t find a cutting continuity anywhere so we had to translate the Czech titles and I wrote English titles based upon those translations. We showed it at the 1969 or 1970 New York Film Festival and elsewhere. The foreign negative seemed to have been edited rather crudely from out-takes (there was only one camera) and when I showed our finished version to Karl Brown, he very politely said that he thought it bore sparse relation to the original domestic version, that in fact it was pretty awful, and was certainly no “lost masterpiece” in its present form. All we have today is a suggestion of what the film might have been. The preservation element is at MoMA.”

Now fortunately most films from the silent era survive in material better than this, but most also do not survive in the original camera negative or a pristine, well-printed 2nd generation 35mm positive. They lie somewhere in-between. For a film like A Fool There Was, which lies on the more compromised end of that spectrum, one needs to keep this in mind, and be generous towards it, that it can no longer speak to you in quite the way it was once able.

Caveat

Now, this whole time we have been talking about films, but I am showing you video clips of films which have further been subjected to the compression of a streaming platform. I have had people scoff and roll their eyes at the idea that movies produced on film should ideally be seen in a theater, projected from film, as opposed to being watched on a television, computer monitor, or — God forbid — a smart phone. But I hope you will take, not just my word, but the word of many others who have spent much of their lives devoted to studying the art of film, that movies made for theatrical exhibition are best experienced in that context, in as close to their original form as is possible, whenever the opportunity arises. But this is another subject deserving of its own video. So for now, I will leave it at that.

conclusion

But, to distill the points I’ve been trying to make in this series, films from the silent era (or what survives of them) will look different because they were made with different equipment, materials, techniques, and aesthetic aims. But a viewer must also take into consideration that what they are viewing may look quite different from what the makers intended, either due to the quality of the surviving prints, or the quality of the material used in the presentation (live or on video) that they are accessing.

YouTuber @bkrewind recently published a video essay comparing the various versions of Nosferatu, in light of Robert Eggers’ 2024 remake, and stated that the original 1922 version could be seen “literally anywhere.” Which is true, you can find many free options among tubitv.com, Youtube, Archive.org and others, but most of these options do not show the film at its best. I’m sure the popularity of Robert Eggers’ new film has led many people to watch the original Nosferatu, as their first exposure to silent film. I have many negative comments such as “the original is shit.” (I don’t remember where I read that. It might have been Letterboxd.) Viewing a subpar presentation is not going to help its reputation among the uninitiated.

Silent Film stays out of the public consciousness for most people in a way that most other arts do not. Even people who love film often give the silent era short shrift. I have heard a well-respected cinema academic state that “1939 was the year the movies reached maturity!” – Implying that all that came before were simply juvenilia. No one speaks of other forms of art this way. No one walks through a gallery of Medieval Christian Art and thinks, “this was pretty good for back then, but it wouldn’t reach maturity until the 18th century.” To a certain extent, I understand what the comment regarding 1939 is aiming at. As a commercial product, the forms, expectations, and tropes of film were firmly established — but this is also what makes quite a lot of mainstream filmmaking after the silent era less interesting for me. There was far less allowance for risk and experimentation in form or content, because by 1939, filmmaking had become to a large extent producer centered, and they had a good grasp on what they felt worked with most audiences, and rarely deviated.

With film, it seems to be assumed that techniques and forms that were abandoned in the past were left there because they didn’t work, or something better replaced them. But artists have always returned to older forms for inspiration — for example: the revival of Greek architecture, and the works of Shakespeare or J.S. Bach. And, forgive me if I seem to be beating a dead horse, but the silent film and the silent era are worthy of far deeper exploration than they currently receive, but for most people, may require some mediation to explain what they are seeing (like the wall texts for artworks in a museum).

So, if you are new to silent film (or even if you aren’t, but your acquaintance has been casual), and are used to seeing your movies in deluxe director’s cuts in 4k scans from the original negative, you may have to adjust your expectations, and in the case of a compromised film, be generous and open minded.